You are here

出版物 & 研究

出版物 & 研究

出版物 & 研究

香港賽馬會災難防護應變教研中心的出版物涵蓋了教研中心跟合作夥伴、顯赫學術機構的研究項目,以及有關災難防護和應變的其他研究與開發。

指引列出了教研中心特別揀選的災難管理技術資訊、操作指引和有用工具。

博客提供了一個平台,讓持份者能分享與災難有關的最新動態、意見及經驗分享。

博客文章由作者以個人身份或代表所屬單位撰寫。內容表達的觀點、思維及意見純屬作者個人想法,並不代表香港賽馬會災難防護應變教研中心的立場。

公眾可在尊重知識產權情況下,使用所有資料,並必須適當引述出處。

2019

全球減災風險評估報告》每兩年就減災最新情況、新興趨勢、災難情況及減災進展進行一次全球評估,旨在引起國際社會對災難風險的關注,鼓勵他們在政治及經濟上為減災提供支持。評估報告由聯合國減少災害風險辦公室聯同多方持份者,包括思想家、從業員、專家及創新者發表並研究世界各地的風險狀況。

《全球減災風險評估報告》不但涵蓋災難風險,同時亦考慮到風險的多元性,包括多重層面、不同規模及造成的各種影響。此外,就政府、社區及個體如何理解各自與風險及減災的關係上,報告亦提供最新資料。

閱讀報告全文及網站指南,請瀏覽《全球減災風險評估報告》網站:https://gar.unisdr.org/report-2019

如您希望從報告全文擷取主要訊息,《2019全球減災風險評估報告精要版》已整理十項主要觀察,每項觀察皆與主報告的相應部分有關。《2019全球減災風險評估報告精要版》網站:https://gar.unisdr.org/sites/default/files/gar19distilled.pdf

《2019全球減災風險評估報告精要版》概述主報告中十個主要訊息。

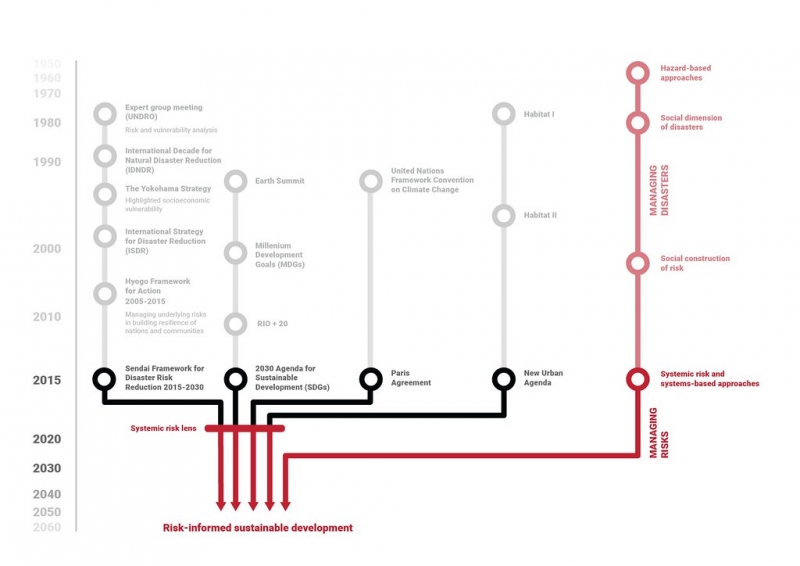

圖片展示全球減災政策議程的演變:穿越時間和空間的旅程

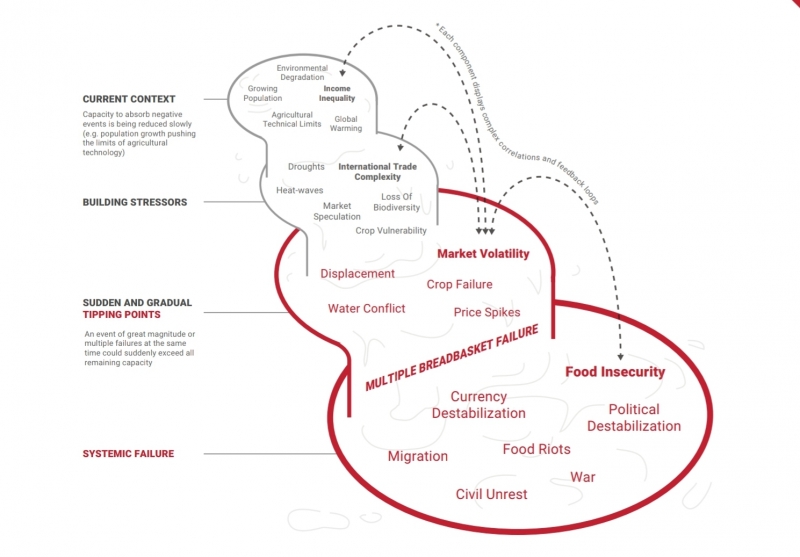

圖片展示系統性風險是如何評估和分析:災害風險可隨著時間形成更多不同的風

[本文只供英語版本]

[本文只供英語版本]

Recently, I attended the 4th Global Summit of Research Institutes for Disaster Risk Reduction (4th GSRIDRR) in the Disaster Prevention Research Institute, at Kyoto University. And I managed to take away with me a few major learnings from the Summit, which I wish sharing here!

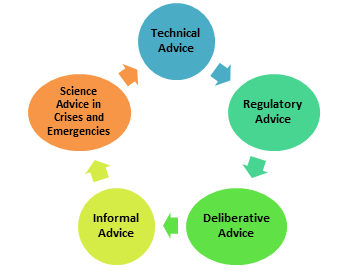

My first learning was about the new scientific challenges to disaster risk reduction and disaster risk management, and there is continuing need to foster uptake of science in government and industries to support implementation – suggestions on what works! I found the organization by Gluckman on the “Five categories of science advice” very comprehensive:

“Five Categories of Science Advice” (Gluckman 2016)

In fact, one of the new scientific challenges is how to close the gaps identified between scientist and decision makers.

The second learning was about the need for holistic scientific advice during crises. According to Professor Virginia Murray, Sendai Framework highlighted the need for holistic scientific advice during crises and emergencies; and the key role of individual science advisor is to be that of “knowledge brokerage” during crises. I was stunned by the comprehensive list of knowledge connections presented, and the continuing establishment of institutes, conferences in disaster risk reduction, as well as the passion in learning by students coming from countries where natural hazards are part of life.

The next learning was about the need in synthesis of knowledge. I could not agree anymore with Professor Murray’s concluding thoughts that there is a need in synthesis of knowledge to inform decision makers at local, national, regional and global levels; we have to learn how to face a new era of risks and to jointly enhance our resilience. Knowledge transfer, co-development of solutions, and continuous uptake of innovative solutions are the ingredients of a more resilient society. However, risk awareness, communication, training and education are imminent for stakeholders at all levels, particularly for urban cities which have been in the comfort zone (fortunately!), such as Hong Kong.

In parallel, I learnt about the interests and demand in structured training and certification in emergency planning, management and disaster preparedness. It resonated with the public’s interests in Hong Kong where there have been varieties of non-accredited training programmes in the discipline offered by various community partners. However, these courses could not be inter-linked to create a synthesis of knowledge due to lack of coordination in their curriculum design and implementation. There was a huge challenge for learners to put the fragmented learning outcomes of these courses into practice and actions.

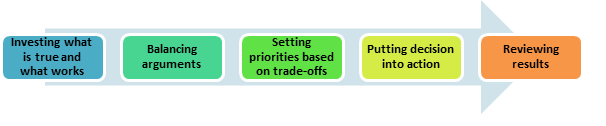

I recalled reading an article on Risk Governance: Application to Urban Challenges (2018). People living in urban environments face multiple risks which range from financial risks, physical risks (natural hazards), technological risks (building structures, infrastructure, hazardous facilities), and social risks (violence, social dissatisfaction).These risks are often inter-linked with each other, hence, need for an integrated governance approach for systemic risks. To put into practice, we need to focus on the steps between knowledge and action by:

Steps Between Knowledge and Action

The last but not the least learning was about the direction of investment in future, that investments should be made in disaster risk reduction for resilience, and there should be a paradigm shift in international funds from post event aids to real prevention, and mitigation action, and national capacity. Investments from local government and philanthropy should increase their weighting in education and training in disaster risk reduction, and to provide guidance for learners to put their knowledge into practice and actions following the concept of risk governance.

References:

Gluckman, P.D (2016). Science Advice to Governments, An Emerging Dimension of Science Diplomacy

Renn, O., Klinke. A., Schweizer, P. Risk Governance: Application to Urban Challenges. Int J Disaster Risk Sci (2018) 9:434-444.

By Dr. Josephine Jim, Hong Kong Jockey Club Disaster Preparedness and Response Institute

[本文只供英語版本]

[本文只供英語版本]

People living in urban environments face multiple risks which range from financial risks, physical risks (natural hazards), technological risks (building structures, infrastructure, hazardous facilities) and social risks (violence, social dissatisfaction).These risks are often inter-linked with each other, hence, the concept of “risk governance” has been developed to provide tools to deal with complex risk situations in urban areas.

A New Framework

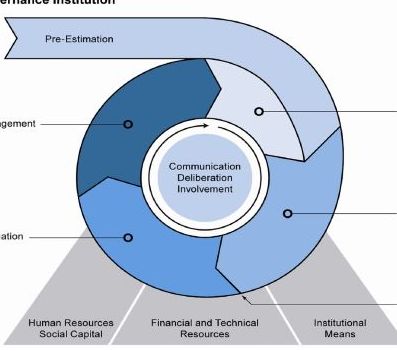

Based on previous work by various scholars, the three major characteristics of risk knowledge that pose specific challenges for risk governance are: Complexity; Scientific Uncertainty and Socio-political Ambiguity. In this article, the International Risk Governance Council (IRGC) suggested a new framework after its original framework in 2005. The new framework structures the risk governance process in 5 steps, accompanied by communication and stakeholder involvement throughout the cycle, together with the effective use of resources:

In the Pre-estimation Phase, relating to risks in urban environments, architects, builders, urban planners, industrial contractors, real estate agents, and the affected population all have different expectations and concerns that should be addressed.

The stages of Interdisciplinary Risk Estimation and Risk Characterisation are: risk assessment and concern assessment which are to match physical risk assessments with human perception. And a risk estimate combines the hazard, exposure and vulnerability assessments into an overall risk profile.

In the context of urban risks, Risk Evaluation includes comparing different management plans and options by considering two sides: the opportunities including potential revenues, and the risks including financial costs and liabilities.

In dealing with urban risks, factors like the degree of complexity, uncertainty and ambiguity determine the options of risk reduction that relate to best available technical knowledge (high complexity), emphasise reversibility and robustness (high uncertainty), and to collect plural value input in case of high ambiguity. Risk Management is to review all relevant data and information generated in risk estimation, characterisation and risk evaluation.

How To Make It Work?

The management agencies’ capability to resolve complexity, clarify uncertainty and handle ambiguity determines the effectiveness of the risk governance process. The keys are communication and deliberation to attain a common understanding of the problems and to address the specific challenges raised; reaching an agreement on the most acceptable risk reduction solutions; and the processes of involving government actors, experts and stakeholders, and the public. Examples of processes are open meetings, interviews, surveys, and reflective processing via mediation, round table, forum, consensus conferences and public advisory committees.

Other Considerations

Risk governance includes a dynamic governance process of continuous and gradual learning and adjustment. There is a need to understand the various concepts that people associate with quality of life in urban environments to find a consensus on risks and benefits, and balancing pros and cons.

This article is summarised from: Renn, O., Klinke. A., Schweizer, P. Risk Governance: Application to Urban Challenges. Int J Disaster Risk Sci (2018) 9:434-444.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13753-018-0196-3

[本文只供英語版本。]

In the event of emergencies, all stakeholders are encouraged to have effective plans which aim at mitigating the social and economic disruption of entire communities. Hence broader community engagement is a key to successful disaster risk management and emergency response. However, there has not been an up-to-date summary of the existing evidence on the enablers and barriers to community engagement in this context.

What did the research involve?

The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control commissioned a study where Ramsbottom et al. reviewed 35 relevant documents published between 2000-2016.

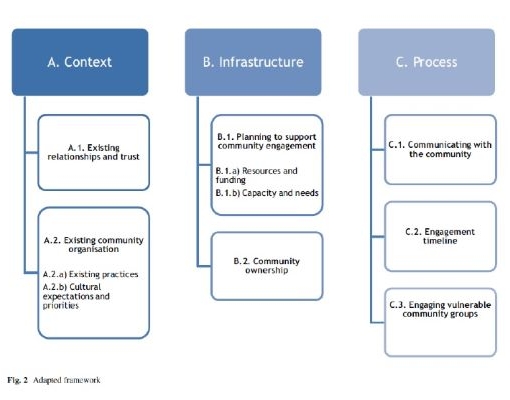

Based on an established framework of barriers and facilitators of community engagement in the public health domain1, they qualitatively analysed these documents and classified different factors into three broad aspects, namely “Context”, “Infrastructure” and “Process”.

What Did the Researchers Find?

Across the 3-phase Emergency Preparedness Cycle (EPC): Anticipation, Response, Recovery, most of the literature focused on community engagement during the anticipation phase, and findings were:

Trust between the communities and institutions is a prerequisite of successful engagement across all phases of the EPC. When designing emergency preparedness programme, it is important to consider local convention and practices, such as methods of obtaining information of decision-making. It is also crucial to understand local culture and value systems. For example, there may be competing priorities, such as social- or healthcare issues, that prevent communities from engaging in emergency response preparedness.

It would be favourable to start by identifying local capacities (e.g. networks of mutual support) and needs to inform planning and prioritisation. Appropriate community empowerment, which would enhance their sense of ownership, would facilitate effective community engagement. In particular, a decentralised approach to allow communities to lead in some planning activities (e.g. identifying priorities) would incentivise sustained action and involvement. Hence, flexible funding allocation is especially favourable, because it could facilitate the development of locally relevant partnerships and programmes.

To build engagement change over different phases of the EPC, communication methods should be tailored to:

- the demographics and cultural characteristics of different community groups across different stages;

- recognise the diversity of the community and dedicate special effort to engage vulnerable sub-population (e.g. linguistically isolated population); and

- ensure the delivery of coherent and consistent information to establish reliability and trust.

What Does it Mean?

Institutions should understand clearly their existing relationships with the targeted communities and reach out to build trust as the foundation of successful engagement.

While it is crucial to identify community-specific resources, needs, and enablers and barriers of engagement at an early stage, engagement should be made throughout the EPC by culturally competent staff, with special dedication to vulnerable groups.

The Way Forward

A two-way communication between institutions and communities should be in place to understand the needs and capacities of communities and promote a sense of ownership, and building a partnership between institutions and communities.

Finally, more research is necessary to understand the enablers and barriers to community engagement during the response and recovery phase of the EPC.

---------------------

1 IHHD. (2015). Review 5: Evidence review of barriers to, and facilitators of, community engagement approaches and practices in the UK. London: Institute of Health and Human Development.

This article is summarised from: Ramsbottom A, O’Brien E, Ciotti L, Takacs J. Enablers and barriers to community engagement in public health emergency preparedness: A literature review. Journal of community health. 2018 Apr 1;43(2):412-20.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5830497/pdf/10900_2017_Article_415.pdf