Days of scorching sun are fuelling Europe’s grid with record-breaking amounts of solar power - but the current heatwave is actually bad news for solar panels.

In Germany, a record amount of electricity was generated by solar power on Sunday, while most of the country was placed under an excessive heat warning.

Even more solar power is expected to be generated in the coming days, as western Europe braces itself for a heatwave many countries have never seen before.

And yet these record-breaking amounts of solar power are far from what the country’s solar panels could have achieved if the temperatures had been a little lower.

While more solar-generated energy could be seen as a silver lining of what’s likely to be a “killer” heatwave, the heat is actually hampering solar panels.

Counter-intuitively, hotter, sunnier days do not equal more power, as rising temperatures actually hinder the capacity of solar panels to collect energy.

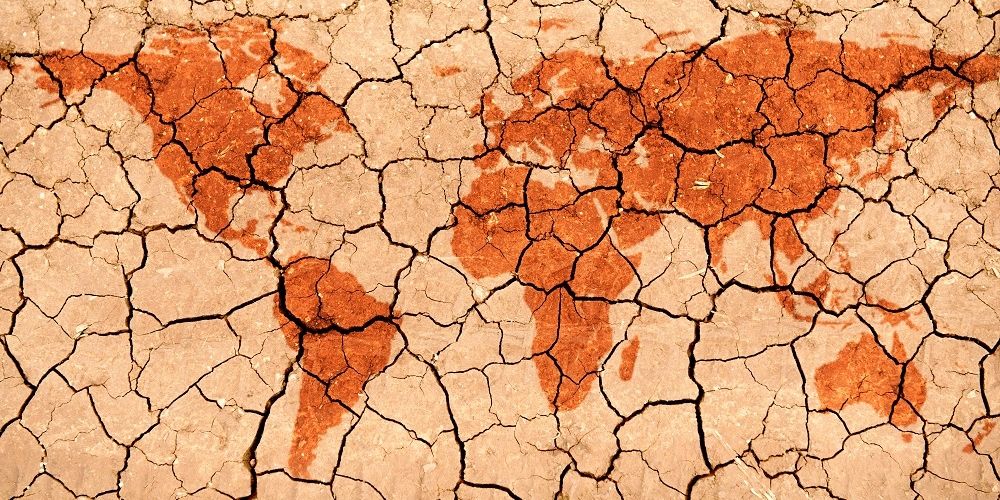

Blasting sun isn't necessarily good news for solar panels - not when that comes with scorching temperatures. - Copyright Canva

How does it work?

Solar panels absorb sunlight with their photovoltaic cells, with the photons soaked in by the panels knocking electrons loose from their atoms and forming an electrical circuit within the semiconductors of the panel, generating a flow of electricity.

Most solar panels are tested at a temperature of 25 degrees Celsius, an ideal temperature at which this process occurs within solar panels under optimal circumstances.

But above this temperature, no matter how bright the sun is shining, efficiency starts going south for the panels.

The heat causes an excessive number of the panel's electrons - the ones responsible for converting energy from the sun into electricity - to be excited, eventually reducing the panel’s generated voltage and its efficiency.

The impact is not minimal. High temperatures can decrease the efficiency of solar panels by 10 to 25 per cent, according to data shared by CED Greentech.

For every degree Celsius more reported by a solar panel, its efficiency drops by 0.5 percentage points, according to Solar.com.

Heatwave in Europe

Across western Europe, temperatures are expected to exceed 40 degrees Celsius.

Unprecedented temperatures are expected in the UK, a country where most houses do not have air conditioning installed. In much of southern Europe, firefighters are already fighting raging blazes sparked by the heat.

There are, obviously, thermal solar panels too, which would not be affected by the increased heat. But these are much rarer panels, especially in homes, and are considered less reliable in generating electricity.

As temperatures continue to rise in the western half of the continent, it’s not a given that the incoming sunny days will be bringing more record-breaking amounts of solar power.

Even though, as people turn to air conditioning to keep cool, demand for electricity is on the rise, renewable solar energy may not be the answer to meeting it.