You are here

Publications & Research

Publications & Research

Publications & Research

The HKJCDPRI Publications Section contains collaborative researches and publications with our partners and renowned academic institutions, and other research and development projects related to disaster preparedness and response.

The Guidelines section contains our selected collection of technical information, operational guidelines and useful tools for disaster management.

The Blog sub-section provides a platform where our team and peers share news and updates, as well as opinions and experiences in building disaster preparedness for the communities.

The blog posts are written by the author in his own personal capacity / affiliation stated. The views, thoughts and opinions expressed in the post belong solely to the author and does not necessarily represent those of Hong Kong Jockey Club Disaster Preparedness and Response Institute.

All resources listed here are freely and publicly available, unless specified otherwise. We ask users to use them with respect and credit the authors as appropriate.

2022

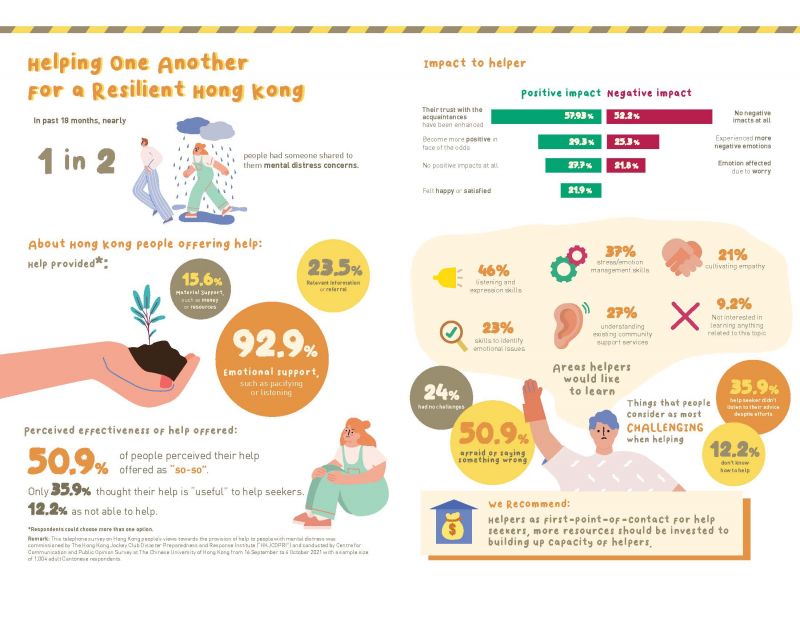

The Hong Kong Jockey Club Disaster Preparedness and Response Institute (“HKJCDPRI”) has commissioned the Centre for Communication and Public Opinion Survey (“CCPOS”) at The Chinese University of Hong Kong (“CUHK”) to conduct an opinion survey about Hong Kong people’s views towards the provision of help to people with mental distress (“the Survey”). Specfically, the Survey aimed to examine the following issues:

- Opinions on providing help to people with mental distress

- Mental distress situation of acquaintance

- Situations of providing help to acquaintance with mental distress

- Opinions on learning how to acquaintance with mental distress

A telephone survey was conducted from 16 September to 4 October 2021 with Hong Kong residents aged 18 or above (Cantonese speakers), which produced a sample size of 1,004 respondents. The main findings of the Survey are summarized as follows:

Opinions on providing help to people with mental distress

- The respondents were asked whether they would be willing to provide help when other people mentioned their mental distress (such as unhappiness, worry, anexiety or anger, etc.) to them. Over seven in ten repsondents (71.9%)said they were willing to help; more than one-fifth (22.5%) said “so-so”; and only a tiny portion (3.2%) said not willing.

- If there were a need for the respondents to help the people with mental distress, over half of them (56.7%) said their confidence level of provding useful help to the people in need was just “so-so”. The proportion of respondents lacking confidence (23.5%) was higher than that of respondents having the confidence (18.3%).

- The respondents thought that the main difficulties of helping the people with mental distress were “don’t know how to help them” (44.3%), “don’t know how to pacify them” (32.0%), “no time” (20.1%) and “don’t understand their troubles” (19.9%)。

Mental distress situation of acquaintance

- Nearly half of the respondents (47.9%) have had their acquaintances (including family members, friends, colleagues, classmates, neighbours or people they met in work) mentioning to them about their mental distress (such as unhappiness, worry, anexiety or anger, etc.) in the past 18 months. And over half of the respondents (52.1%) said they have not encountered this situation.

- Those acquaintances were mainly the “friends” (65.3%), “family members” (31.2%) and “colleages” (20.4%) of the respondents.

- The main sources of mental distress of those acquaintances were about “family” (37.0%) and “work” (36.7%) and as well as “social events” (30.0%) and “the pandemic” (29.2%).

- According to the respondents, those acquaintances mainly had the following symptoms of mental distress: “easy to feel depressed, worried or panicky” (47.9%), “easy to feel anxious, angry or frustrated” (43.6%) and “always suffer from insomnia ” (43.3%).

- Over half of the respondents (51.5%) said that, there was no difference in the number of people mentioning to them about their mental distress between now and before the pandemic. However, more than two-fifths of the respondents (45.7%) said the number of help-seekers has increased; whereas a tiny portion of the respondents (2.4%) said there were fewer help-seekers now.

Situations of providing help to acquaintance with mental distress

- For those respondents who have had their acquaintances mentioning to them about their mental distress in the past 18 months, the overwhelming majority of them (98.1%) have tried/ sometimes have tried to provide some forms of help to the help-seekers, such as listening to their concerns or providing them information or advices. Only a tiny portion of the respondents (1.9%) have not tried to provide any help at all.

- The help being provided by the respondents was mainly “emotional support, such as pacifying or listening”(92.9%). It was then followed by “provding information or referral” (23.5%) and “material support, such as money or resources, etc.” (15.6%).

- In the helping process, the main difficulties encountered by the respondents were “afraid of saying wrong things” (34.4%), “the help-seekers were not listening even I have already spoken a lot” (34.2%) and “don’t know how to help” (31.0%).

- The respondents were asked to evaluate whether their provided help could be able to help the help-seekers. Around half of the respondents (50.9%) said the outcome was only “so-so”. Over three in ten respondents (35.9%) believed that their help was useful for the help-seekers; however, over one in ten respondents (12.2%) believed that their provided help was not able to help the help-seekers.

- Nearly three-fifths of the respondents expressed that having provided help to the acquaintances with mental distress, “their trust with the acquaintances have been enhanced” (57.3%). Nearly three in ten respondents said that they “have become more positive in face of the odds” (29.3%). Moreover, about one-fifth of the respondents “have felt happy or satisfied” (21.9%). However, there was also more than a quarter of the respondents (27.7%) experiencing “no positive impacts at all” in helping others.

- As far as negative impacts are concerned, over half of the respondents (52.2%) said that providing help to the acquaintances with mental distress has caused “no negative impacts” on them. However, over one-fifth of the respondents have said “they have experienced more negative emotions” (25.3%) and “their emotion has been affected because of worry” (21.8%) respectively.

- As mentioned above (point 9), some respondents have not tried/ sometimes have not tried to provide help to the acquaintances with mental distress. Their main reasons were “don’t know how to help” (47.9%), “the relationship with them wasn’t that close” (18.3%), “they may not want me to help them” (11.9%), “just trivial matters; no need to help” (10.7%) and “afraid of being troubled” (7.9%).

Opinions on learning how to acquaintance with mental distress

- Finally, the Survey asked all respondents what knowledge or skills they would like to learn for helping people with mental distress. The top choice was “listening and presentation skills” (46.2%), which was followed by “the methods of reducing stress or releasing emotions (36.6%), understanding“existing supportive services in the community” (26.8 %), “identifying emotional health problems” (22.7%) and “cultivating empathy” (20.6%). However, close to one in ten repsondents (9.2%) have expressed no interest in all above-mentioned items.

[This article is only available in Chinese.]

[This article is only available in Chinese.]

香港賽馬會災難防護應變教研中心( 教研中心) 堅信「防災教育,從小做起」,自2019 年起積極與業界和學界合作,研發有趣又貼近生活的教學方法與教材,培養幼兒的防災知識、技能和態度,為應對未來的危難事件作好充分的身心準備。

教研中心在2020-21學年夥拍香港教育大學幼兒教育學系的研究團隊,開展一項名為「幼稚園推行防災教育課程的成效與挑戰」的研究項目。此研究旨在探討幼稚園校本防災教育課程對幼兒的批判性思維、解決問題和情緒管理能力的影響,並透過分析學校,社區和家長等不同層面和因素,了解本地幼稚園推行防災教育的成效和挑戰,從而加強學前兒童對防災和應災的知識、技能和態度。

綜合各持份者意見及研究結果,校長、教師和家長均認同推行幼兒防災教育的好處。從幼兒在活動中的表現、同儕之間的對話和學習評估表現中發現,幼兒的解難能力、自我保護和求生意識,於參與由教研中心舉辦的「幼稚園創新防災教材研發計劃」後均相對有所提升。

這份研究報告將有助了解香港幼兒防災教育的定位與發展方向,並就社會不同各持份者提出相關建議,具重要參考價值。相關內容及意見已提交教育局參閱。

詳細報告內容 (只限中文版) :https://www.hkjcdpri.org.hk/flipbook/kinderedu_researchreport/mobile/

2021

2020

In times of Sudden Onset Disaster (SOD), timely emergency medical services are crucial to the affected communities. Being seen as one of the most important approach in emergency situations, emergency medical teams have a long history of responding to SODs such as the Haiti earthquake, the Indian Ocean Tsunami and the floods in Pakistan.

The World Health Organization has launched the Emergency Medical Teams (EMTs) initiative, formerly known as Foreign Medical Teams (FMTs) initiative, to introduce a classification, minimums standards and a registration system for EMTs that may provide quality healthcare services arriving within the aftermath of a SOD. The initiative historically focused on trauma and surgical needs, but outbreaks in Africa (Ebola) and Asia (diphtheria) have shown that EMTs’ responses are also valuable in responses to outbreaks and other forms of emergency which exceed the capacity of the local health system. [1]

SODs like earthquakes could cause mass casualty, and the surge in the needs for healthcare services could evolve within days, if not hours. In the article titled “Decision Support Framework for Deployment of Emergency Medical Teams after Earthquakes”, Bartolucci et. al. has summarized the evolvement of health needs in earthquake situation and observed that emergency surgical conditions reduced by 50% within the first week after the onset of the earthquake. The number of trauma cases dropped to less than 10% after 15 days.

According to another report published by WHO and the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) in 2017, The Regulations and Management of International Emergency Medical Teams [2], the timing of deployment (the time that the EMT is ready to attend to its first patient) in most of the SODs was not recorded properly. The study summarized some available data of several recent emergency operations, and has shown that the timing of deployment could vary from 2 days to 18 days. Yet in an emergency, the healthcare needs on ground may have changed drastically after 18 days.

Bartolucci et. al. continued to summarize experts’ opinions with a Delphi study followed by literature search and created an evidence-based framework for EMT coordinators and decision makers. The framework targets to facilitate decisions making in the configuration and capacity of the EMT. It can also facilitate a better estimation on the potential needs on ground so that EMTs can provide a timelier and quality healthcare service to the affected communities.

The article and the decision-making framework are available in the link below:

Decision Support Framework for Deployment of Emergency Medical Teams after Earthquakes

Reference:

[1] Fact Sheet: Emergency Medical Teams (EMTs), World Health Organization, May 2019

[2] The Regulations and Management of International Emergency Medical Teams, World Health Organization (WHO) & International Federatio of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC), June 2017

Elaine FONG

Manager (Professional and Knowledge Management)

Hong Kong Jockey Club Disaster Preparedness and Response Institute

*This article originates from a research funded by the Hong Kong Jockey Club Charities Trust within the collaborative project “Training and Research Development for Emergency Medical Teams with reference to the WHO Global EMTs initiative, classification and standards” between the Humanitarian and Conflict Response Institute (HCRI) and the Hong Kong Jockey Club Disaster Preparedness and Response Institute (HKJCDPRI)”.