You are here

Publications & Research

Publications & Research

Publications & Research

The HKJCDPRI Publications Section contains collaborative researches and publications with our partners and renowned academic institutions, and other research and development projects related to disaster preparedness and response.

The Guidelines section contains our selected collection of technical information, operational guidelines and useful tools for disaster management.

The Blog sub-section provides a platform where our team and peers share news and updates, as well as opinions and experiences in building disaster preparedness for the communities.

The blog posts are written by the author in his own personal capacity / affiliation stated. The views, thoughts and opinions expressed in the post belong solely to the author and does not necessarily represent those of Hong Kong Jockey Club Disaster Preparedness and Response Institute.

All resources listed here are freely and publicly available, unless specified otherwise. We ask users to use them with respect and credit the authors as appropriate.

2019

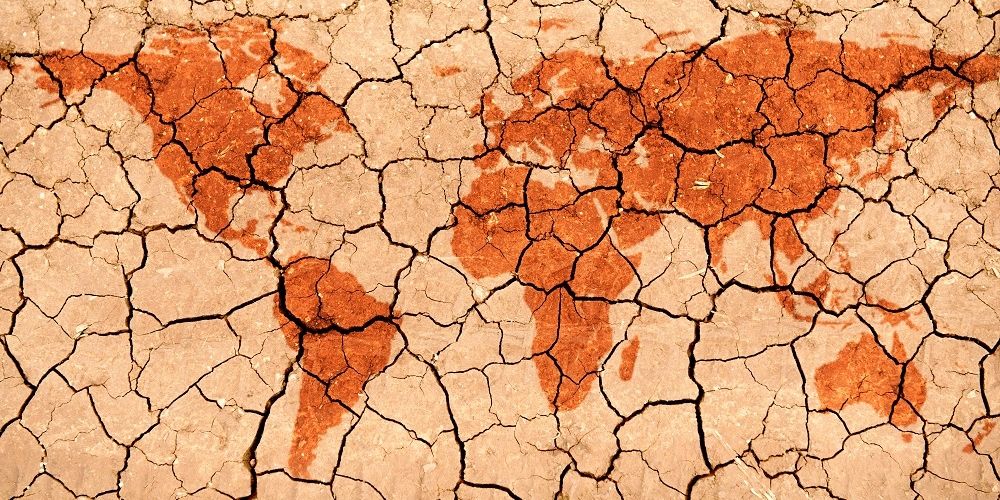

The Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction (GAR) is a biennial global assessment of disaster risk reduction highlighting latest updates, emerging trends, disaster patterns and progress in reducing risk. It aims to focus international attention on the issue of disaster risk and encourage political and economic support for disaster risk reduction. The GAR is produced by the UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction in collaboration and consultation with a wide range of stakeholders, with thinkers, practitioners, experts and innovators to investigate the state of risk across the globe.

The GAR19 (the GAR 2019) moves beyond disaster risk to consider the pluralistic nature of risk: in multiple dimensions, at multiple scales and with multiple impacts. It provides an update on how we – as governments, as communities and individuals – understand our relationship with risk and its reduction.

The Full Report and a guided tour are available at the GAR19 Website: https://gar.unisdr.org/report-2019

Want some quick take-home messages from the detailed full report? The GAR19 Distilled collates 10 take-home observations from GAR19. Each observation is linked to the relevant section in the GAR19 main report. The link to GAR19 Distilled: https://gar.unisdr.org/sites/default/files/gar19distilled.pdf

The GAR19 Distilled offers 10 take-home messages from the full report.

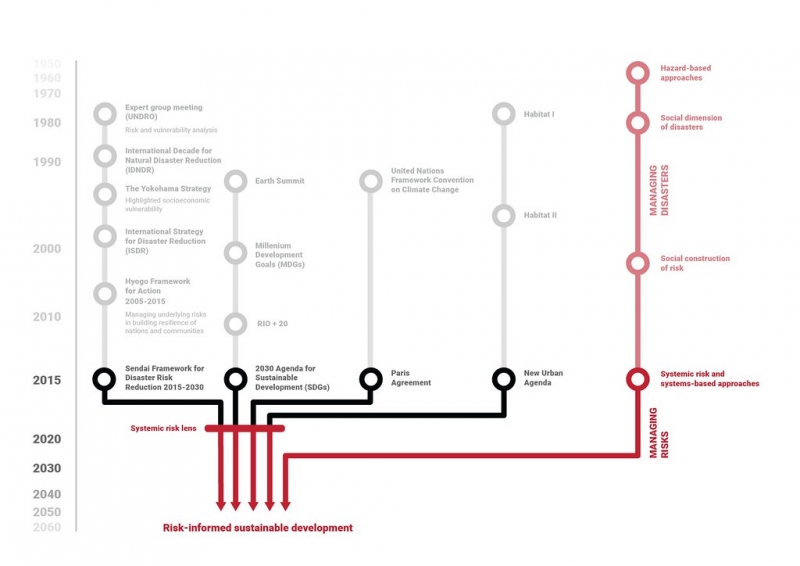

An illustration showing evolution of the global policy agenda for disaster risk reduction: A journey through time and space.

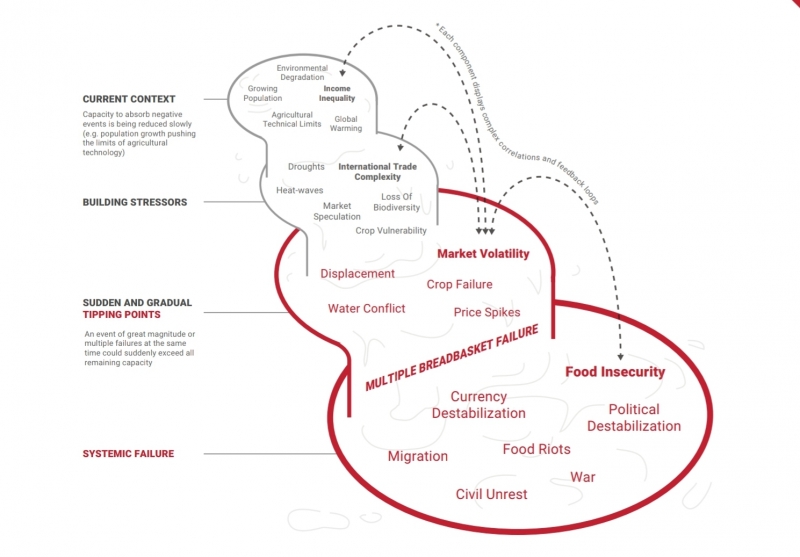

An illustration showing how systemic risks are assessed and analysed: Mapping the topology of risk through time.

by HKJCDPRI

Recently, I attended the 4th Global Summit of Research Institutes for Disaster Risk Reduction (4th GSRIDRR) in the Disaster Prevention Research Institute, at Kyoto University. And I managed to take away with me a few major learnings from the Summit, which I wish sharing here!

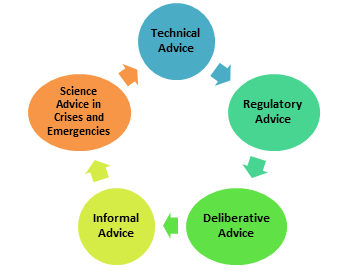

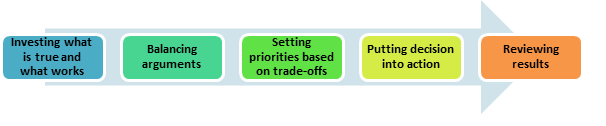

My first learning was about the new scientific challenges to disaster risk reduction and disaster risk management, and there is continuing need to foster uptake of science in government and industries to support implementation – suggestions on what works! I found the organization by Gluckman on the “Five categories of science advice” very comprehensive:

“Five Categories of Science Advice” (Gluckman 2016)

In fact, one of the new scientific challenges is how to close the gaps identified between scientist and decision makers.

The second learning was about the need for holistic scientific advice during crises. According to Professor Virginia Murray, Sendai Framework highlighted the need for holistic scientific advice during crises and emergencies; and the key role of individual science advisor is to be that of “knowledge brokerage” during crises. I was stunned by the comprehensive list of knowledge connections presented, and the continuing establishment of institutes, conferences in disaster risk reduction, as well as the passion in learning by students coming from countries where natural hazards are part of life.

The next learning was about the need in synthesis of knowledge. I could not agree anymore with Professor Murray’s concluding thoughts that there is a need in synthesis of knowledge to inform decision makers at local, national, regional and global levels; we have to learn how to face a new era of risks and to jointly enhance our resilience. Knowledge transfer, co-development of solutions, and continuous uptake of innovative solutions are the ingredients of a more resilient society. However, risk awareness, communication, training and education are imminent for stakeholders at all levels, particularly for urban cities which have been in the comfort zone (fortunately!), such as Hong Kong.

In parallel, I learnt about the interests and demand in structured training and certification in emergency planning, management and disaster preparedness. It resonated with the public’s interests in Hong Kong where there have been varieties of non-accredited training programmes in the discipline offered by various community partners. However, these courses could not be inter-linked to create a synthesis of knowledge due to lack of coordination in their curriculum design and implementation. There was a huge challenge for learners to put the fragmented learning outcomes of these courses into practice and actions.

I recalled reading an article on Risk Governance: Application to Urban Challenges (2018). People living in urban environments face multiple risks which range from financial risks, physical risks (natural hazards), technological risks (building structures, infrastructure, hazardous facilities), and social risks (violence, social dissatisfaction).These risks are often inter-linked with each other, hence, need for an integrated governance approach for systemic risks. To put into practice, we need to focus on the steps between knowledge and action by:

Steps Between Knowledge and Action

The last but not the least learning was about the direction of investment in future, that investments should be made in disaster risk reduction for resilience, and there should be a paradigm shift in international funds from post event aids to real prevention, and mitigation action, and national capacity. Investments from local government and philanthropy should increase their weighting in education and training in disaster risk reduction, and to provide guidance for learners to put their knowledge into practice and actions following the concept of risk governance.

References:

Gluckman, P.D (2016). Science Advice to Governments, An Emerging Dimension of Science Diplomacy

Renn, O., Klinke. A., Schweizer, P. Risk Governance: Application to Urban Challenges. Int J Disaster Risk Sci (2018) 9:434-444.

By Dr. Josephine Jim, Hong Kong Jockey Club Disaster Preparedness and Response Institute

People living in urban environments face multiple risks which range from financial risks, physical risks (natural hazards), technological risks (building structures, infrastructure, hazardous facilities) and social risks (violence, social dissatisfaction).These risks are often inter-linked with each other, hence, the concept of “risk governance” has been developed to provide tools to deal with complex risk situations in urban areas.

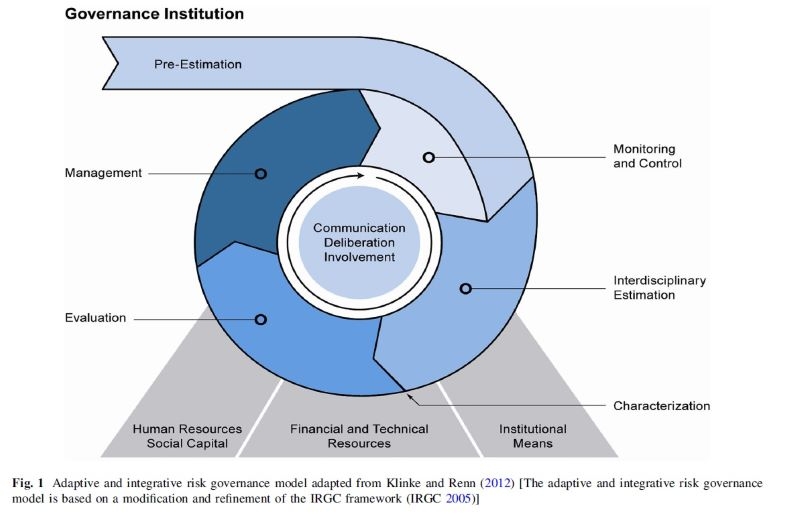

A New Framework

Based on previous work by various scholars, the three major characteristics of risk knowledge that pose specific challenges for risk governance are: Complexity; Scientific Uncertainty and Socio-political Ambiguity. In this article, the International Risk Governance Council (IRGC) suggested a new framework after its original framework in 2005. The new framework structures the risk governance process in 5 steps, accompanied by communication and stakeholder involvement throughout the cycle, together with the effective use of resources:

In the Pre-estimation Phase, relating to risks in urban environments, architects, builders, urban planners, industrial contractors, real estate agents and the affected population all have different expectations and concerns that should be addressed.

The stages of Interdisciplinary Risk Estimation and Risk Characterisation are: risk assessment and concern assessment which are to match physical risk assessments with human perception. And a risk estimate combines the hazard, exposure and vulnerability assessments into an overall risk profile.

In the context of urban risks, Risk Evaluation includes comparing different management plans and options by considering two sides: the opportunities including potential revenues and the risks including financial costs and liabilities.

In dealing with urban risks, factors like the degree of complexity, uncertainty and ambiguity determine the options of risk reduction that relate to best available technical knowledge (high complexity), emphasise reversibility and robustness (high uncertainty) and to collect plural value input in case of high ambiguity. Risk Management is to review all relevant data and information generated in risk estimation, characterisation and risk evaluation.

How To Make It Work?

The management agencies’ capability to resolve complexity, clarify uncertainty and handle ambiguity determines the effectiveness of the risk governance process. The keys are communication and deliberation to attain a common understanding of the problems and to address the specific challenges raised; reaching an agreement on the most acceptable risk reduction solutions; and the processes of involving government actors, experts and stakeholders, and the public. Examples of processes are open meetings, interviews, surveys and reflective processing via mediation, round table, forum, consensus conferences and public advisory committees.

Other Considerations

Risk governance includes a dynamic governance process of continuous and gradual learning and adjustment. There is a need to understand the various concepts that people associate with quality of life in urban environments to find a consensus on risks and benefits and balancing pros and cons.

This article is summarised from: Renn, O., Klinke. A., Schweizer, P. Risk Governance: Application to Urban Challenges. Int J Disaster Risk Sci (2018) 9:434-444.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13753-018-0196-3

In the event of emergencies, all stakeholders are encouraged to have effective plans which aim at mitigating the social and economic disruption of entire communities. Hence broader community engagement is a key to successful disaster risk management and emergency response. However, there has not been an up-to-date summary of the existing evidence on the enablers and barriers to community engagement in this context.

What did the research involve?

The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control commissioned a study where Ramsbottom et al. reviewed 35 relevant documents published between 2000-2016.

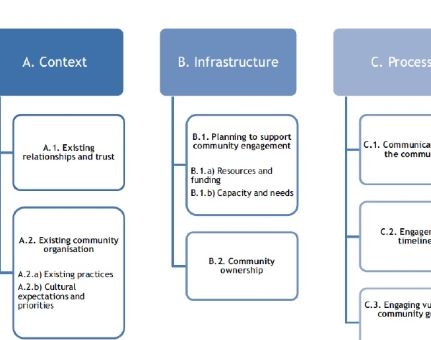

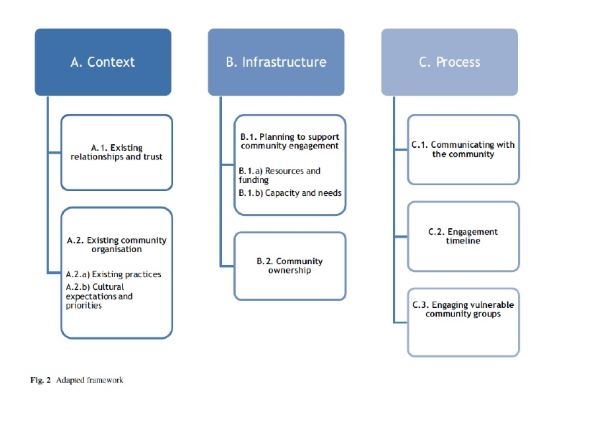

Based on an established framework of barriers and facilitators of community engagement in the public health domain1, they qualitatively analysed these documents and classified different factors into three broad aspects, namely “Context”, “Infrastructure” and “Process”.

What Did the Researchers Find?

Across the 3-phase Emergency Preparedness Cycle (EPC): Anticipation, Response, Recovery, most of the literature focused on community engagement during the anticipation phase, and findings were:

Trust between the communities and institutions is a prerequisite of successful engagement across all phases of the EPC. When designing emergency preparedness programme, it is important to consider local convention and practices, such as methods of obtaining information of decision-making. It is also crucial to understand local culture and value systems. For example, there may be competing priorities, such as social- or healthcare issues, that prevent communities from engaging in emergency response preparedness.

It would be favourable to start by identifying local capacities (e.g. networks of mutual support) and needs to inform planning and prioritisation. Appropriate community empowerment, which would enhance their sense of ownership, would facilitate effective community engagement. In particular, a decentralised approach to allow communities to lead in some planning activities (e.g. identifying priorities) would incentivise sustained action and involvement. Hence, flexible funding allocation is especially favourable, because it could facilitate the development of locally relevant partnerships and programmes.

To build engagement change over different phases of the EPC, communication methods should be tailored to:

- the demographics and cultural characteristics of different community groups across different stages;

- recognise the diversity of the community and dedicate special effort to engage vulnerable sub-population (e.g. linguistically isolated population); and

- ensure the delivery of coherent and consistent information to establish reliability and trust.

What Does it Mean?

Institutions should understand clearly their existing relationships with the targeted communities and reach out to build trust as the foundation of successful engagement.

While it is crucial to identify community-specific resources, needs, and enablers and barriers of engagement at an early stage, engagement should be made throughout the EPC by culturally competent staff, with special dedication to vulnerable groups.

The Way Forward

A two-way communication between institutions and communities should be in place to understand the needs and capacities of communities and promote a sense of ownership, and building a partnership between institutions and communities.

Finally, more research is necessary to understand the enablers and barriers to community engagement during the response and recovery phase of the EPC.

---------------------

1 IHHD. (2015). Review 5: Evidence review of barriers to, and facilitators of, community engagement approaches and practices in the UK. London: Institute of Health and Human Development.

This article is summarised from: Ramsbottom A, O’Brien E, Ciotti L, Takacs J. Enablers and barriers to community engagement in public health emergency preparedness: A literature review. Journal of community health. 2018 Apr 1;43(2):412-20.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5830497/pdf/10900_2017_Article_415.pdf